January 9th was my birthday, the occasion for me to choose what I wanted to do. What I wanted to do was be in Walla Walla to visit my brother, Ian. It was a Tuesday and Karen was at work and Ian had stuff to do at home in the morning. We all planned to get together and celebrate in the evening, so Pedro and I entertained ourselves by driving out to the Whitman Mission National Historic Site, which was only 15 minutes’ drive from our hotel in the center of Walla Walla.

Ian and Karen had recently toured there and didn’t need to see it again so soon. The site was free to park, free to enter both the Visitor’s Center and to walk the grounds, which are something of an outdoor museum.

It was crisply cold and very windy, so to minimize our time outside, we decided to learn all we could while inside, and then hopefully that would make our time outside more efficient. We were greeted by a very friendly Park Ranger, who noted that it is a federal site, which probably explains the relatively high quality despite the free entrance. She recommended seeing the short movie first, which tells the story of the site. After the movie we saw all the exhibits in the small visitor center museum. As Ian had warned us earlier, and the ranger alluded to, the Historic Site is in the midst of a transition of sentiments.

It appears as though the site was originally set up to recognize the wrongful murder of innocent white settlers by indigenous savages. Today, parks in the US are doing a much better job of trying to tell nuanced stories that present multiple perspectives.

Disclaimer signs on every single information board say: “This panel includes one-sided representations of history and perpetuates harmful stereotypes. These depictions were wrong when created and are still wrong today. Truthfully telling this history requires the inclusion of multiple perspectives. We are updating these signs in partnership with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.” (The reason it lists the Umatilla Tribe is because the Cayuse tribe joined the Umatilla tribe to sign a treaty after the numbers of both were decimated due to disease. Today they share a reservation.)

What follows are my own words telling the story of what we learned in the movie and literature at the site: The movie explained that the United States was having one of its evangelist surges, and religious leaders began espousing the idea that it was the duty of the faithful to take Christianity to the Indians. There was even a story that Indians had expressed a desire to learn about the Bible (that part was not true). Many Americans took this as a call to action. I respect their bravery, for these people walked the talk. In 1836, Presbyterians Mr. and Mrs. Whitman were young, educated, and from loving supportive families, and yet off they went into who knows what, prepared to leave their families behind forever, all in the service of their God. It’s super impressive, despite being wildly misdirected.

The Whitmans asked for and received permission from the Cayuse to build their home on Cayuse land, near where the Cayuse lived during the winter. (Thanks Bushboy from bushboys world for asking for a pronunciation. I have not been instructed by a tribal person, but the common pronunciation is like KAI yoos, emphasis on the first syllable.) The Whitmans worked very hard in difficult conditions to establish themselves and got along great at first with the Cayuse tribe in what is now Walla Walla. Indians showed up for their sermons, hoping to learn something about the White Man’s God, and see what He might have to say about things. Unfortunately, their style of proselytizing was to proclaim hellfire and damnation if they rejected God’s teachings. The Cayuse didn’t quite understand and thought Mr. Whitman was calling violence upon them. They lost interest and quit coming to the sermons.

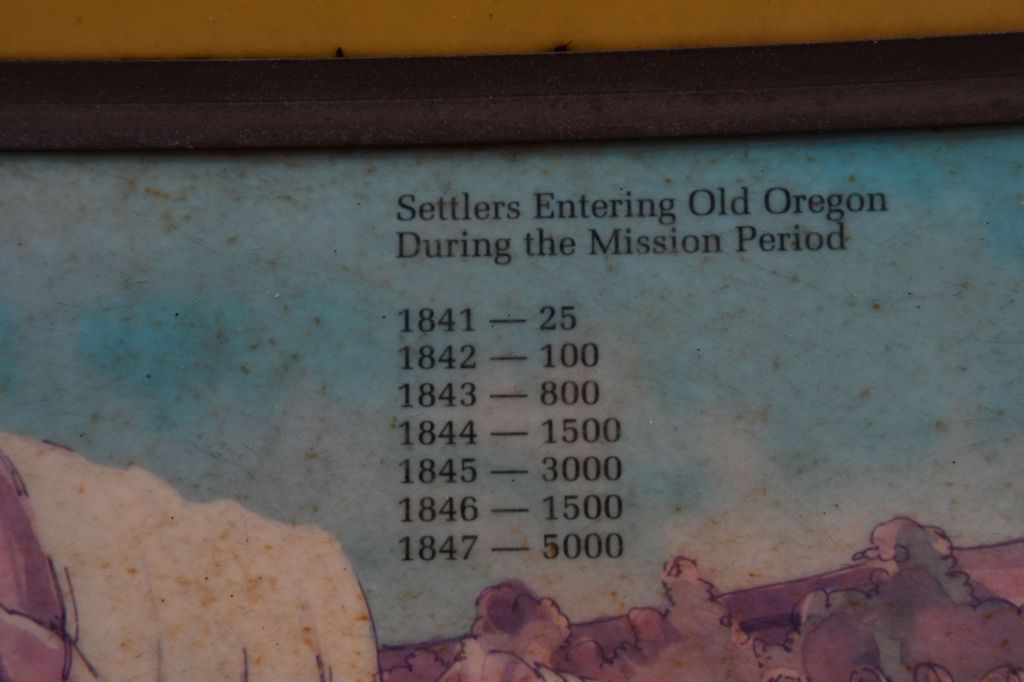

Backers of the missions heard about the trouble getting Natives converted, and decided to shut down a few missions in the area, the Whitman’s included. Mr. Whitman made the crazy trip BACK to St. Louis to beg for funding and political support to remain open, and he won them over. On his return trip in 1843, Mr. Whitman brought a new group of 1,000 pioneers with him.

In this early American social climate, to return home was not an option for the Whitmans. A returned missionary was considered a failed missionary. They were not prepared to face pity and ostracism back home. They had to stay. So, they decided that God’s REAL mission for them was to administer to the many other settlers coming through. They had established their home and mission directly adjacent to the Oregon Trail, a famous route that nearly every European settler used in the early days to move into the west, called The Oregon Territory at that time. One way that the Whitmans helped is when orphans arrived, parents having died somehow along the journey, the Whitmans adopted them.

As more and more and more settlers came in and took Cayuse land, they brought diseases with them. Mr. Whitman had been trained as a medical doctor and had brought medicine with him. He knew about the diseases and knew how to treat them. But these were diseases that indigenous people had never been exposed to, which made them extremely vulnerable. In 1847 there was a terrible outbreak of measles. Among the Cayuse, a tiwaat – a person who healed – must follow certain ethical rules, which Mr. Whitman was aware of. He knew that a tiwaat was believed to have the ability to cure and also to kill, and the penalty for malpractice was death. The Whitmans converted a part of their mission building to a clinic and quarantine, and began providing medical care to everyone who needed it. Unfortunately, Mr. Whitman seemed to be unable to cure the Cayuse, while he did have the skills to cure the settlers. It didn’t make sense to the Cayuse and they became suspicious.

This was all in the setting of more and more settlers showing up each Autumn, and wanting to build homes on Cayuse land. They recalled that Mr. Whitman himself had brought many of them. It seemed as though the White people wanted to dominate the area, maybe even completely take their land away from them.

There were heated discussions and the Cayuse were fed up. They demanded over and over for the Whitmans to leave town, for more than a year. They came to believe that Mr. Whitman was poisoning their people, especially the children. He would feed them mysterious liquids from his bottles and then the children would die. Cayuse leaders even threatened Mr. Whitman, letting him know that he was in danger if he and his wife didn’t leave. As I mentioned earlier, the Whitmans had some powerful reasons to stay, even though they were scared.

The measles epidemic was devastating, and killed 50% of the Cayuse. If I remember correctly, all three of the Cayuse chief’s children died at the same time. That was the last straw. In November 1847 (after five thousand settlers had just come in on the Oregon Trail in the few months preceding), Cayuse attacked the compound, killing 11 people, including the Whitmans, and kidnapped many others, including their 10 adopted children. The Hudson’s Bay Company paid ransoms to get the Cayuse to release the hostages. That was the end of the mission.

As we all know, that was not the end of the Cayuse troubles with White settlers. The Cayuse War followed, as settlers sought revenge. I checked the Internet and a 2010 Census notes that only 304 people in the U.S. identify themselves as Cayuse.

The obelisk at the top of the hill says only: “Whitman.” So we looked around as long as we could bear the wind, then continued along the path to the other side of the hill where we had been told we would find a gravesite.

I’m glad we stopped here. It was very educational, and it seems fair. I’ve heard this story so many times, and it’s a tragedy that it happened so often. White settlers with decent intentions and Native Americans with decent intentions just did not understand each other. The ensuing failure to communicate clearly to each other, or to understand the completely different values systems, made them so suspicious of each other. In the end, both sides thought violence was the only way to communicate. Aside from the good people trying to do their best, in every situation there were a few awful people trying to gain power and wealth by using everyone else. It’s heartbreaking that humans always, always fall back on violence when they are confused and scared. I hate it. But I do get it.

We got back into the car shivering and chilled to the marrow. We went over to Ian’s house to pick him up and head next to the Fort Walla Walla museum for the second half of the day. That will be in my next post.

Such a shocking story to have been repeated so often

Agreed. I appreciate how hard the site here has tried to show the humanity of everyone involved, and counter the original messaging.

That is far better than simply trying to erase history.

That was fabulous. The parallels between here and there are quite similar. White bible bashing do gooders 🙄

Is the tribes name sounded as it is written Cay-use but I bet the phonetics are very different.

For some strange reason the book Savage Sam by Fred Gipson came to mind. Savage Sam is a son of Old Yella and is a story of boys being kidnapped by Apache It is a kids book I read when I was a library nerd lol

Have you heard of it?

That’s a great question about pronunciation, Brian. I am going to edit my post to add that in. The common pronunciation of the tribal name is like KAI yoos, with the emphasis on the first syllable. This name came from the French trappers in the area who called them Cailloux. Their name for themselves is believed to have been Liksiyu. Today they approve of the name their neighbor tribe gave them, which is Weyiiletpuu.

I did not read Savage Sam, but I also did not read Old Yeller. Though I read everything I could get my hands on as a kid, someone told me that Old Yeller was sad because the dog died. I never read it because I didn’t want to be sad, ha ha. I just looked at the plotline, and it looks interesting.

Thanks for the way to say their name and a bit of history as well 👍😀

Savage Sam is a good read. I didn’t read Old Yella either

Over and over and over, Crystal. My ancestors were devout Presbyterians, indeed founders of Presbyterianism in America, and martyrs of Presbyterianism in Scotland. And they were pioneers who came to Washington and Oregon in the 1800s. They likely knew the Whitmans. I don’t know if you remember, but the family was also married into the Applegate family, who created the Applegate Trail. I don’t comprehend missionary zeal. Or fundamentalism. It is so far outside of my world, that I have a hard time looking at it rationally in a balanced way. Or excusing it. I always remember my father wishing three things for me: That I would get married and have children, check, that I would take up photography, check, and that I would become a good Christian boy. I always figured that two out of three wasn’t bad. Grin.

I do remember your connection to the Applegates, who were an important family in the early settlement here, but I did not recognize the name Whitmans. They probably did know of each other, and since the Applegates went further along the Trail, I wonder if they stopped at the mission for a while, then went on through. As for the zeal, I do understand it and I think it’s because of my Mormon family, who truly believed to the depths of their hearts that they were going to their heaven and I was not, and they believed that families get to hang out together for eternity in heaven, and they would literally cry while trying to get me to become a Mormon. They honestly expected to have an eternity of heartache while missing absent family members. So in that context, I can understand a different perspective, of people imagining 1) that Indians would be deprived of something so wonderful as heaven without their preaching, and 2) that they themselves would be fulfilling their obligation to their beloved deity by trying to convert them. You are absolutely right that two out of three is a success! Your dad must have been proud of the man you became, even if you didn’t become the perfect man.

The mind is a marvelous thing (or perhaps not so marvelous) in what it can believe, Crystal. And I’m sure that true believers have as hard of a time understanding my perspective as I have understanding theirs.

As a teenager, for a while, however, I was a very serious Episcopalian, to the degree they were pushing me to become a priest. That went south when I learned how much of Christianity was based on earlier mythologies.

My dad and I got along very well, even when I was challenging him about the world being 6000 years old. 🙂