The Atlas Obscura site mentions a museum of Chinese artifacts in John Day – a small town in the middle of nowhere Oregon. The Kam Wah Chung Chinese museum seemed quite unlikely, but is apparently one of the major turn-of-the-century collections of Chinese goods and documents in all of North America. At one time, the Chinatown of John Day was third in size only behind San Francisco and Seattle. I made a mental note to go there and see what this was all about. While visiting with my old music teacher at his home the day before, he asked what each of us were doing the next day. I said I would be heading for John Day. “OH! Have you been to the museum?” he asked. I was delighted that he already knew where I planned to go. I told him I had never been, but was planning on it.

The Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site is managed by Oregon State Parks. It has a wonderful story and you really MUST go if you are ever in central Oregon. I summarize the story below, as well as I can.

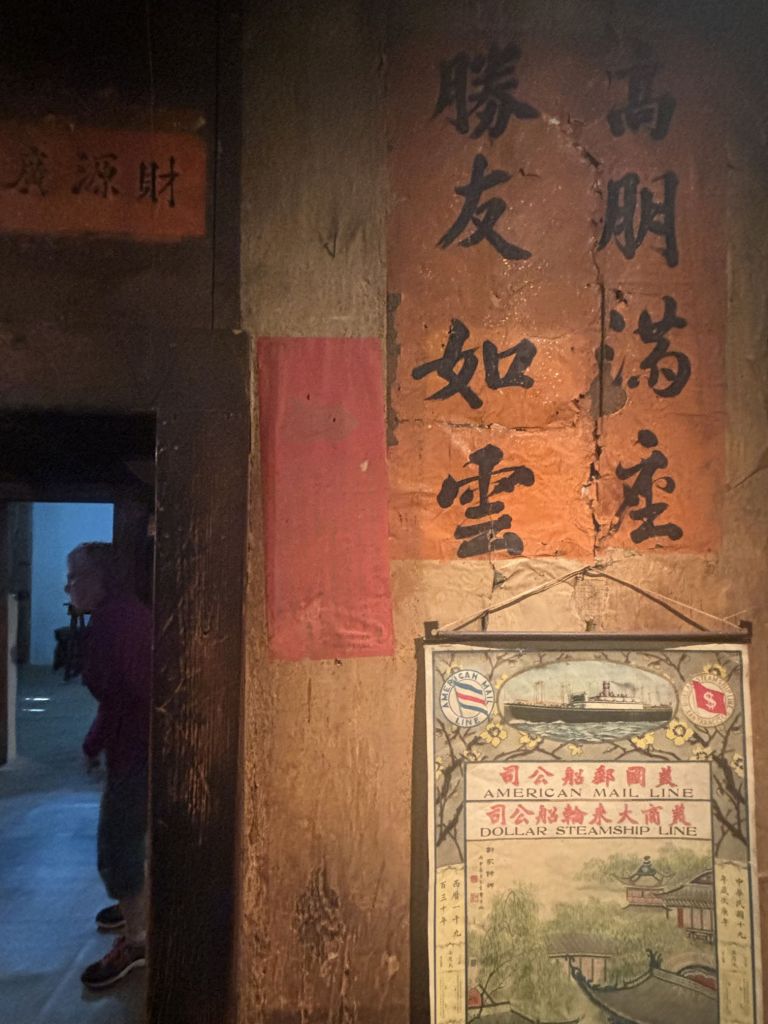

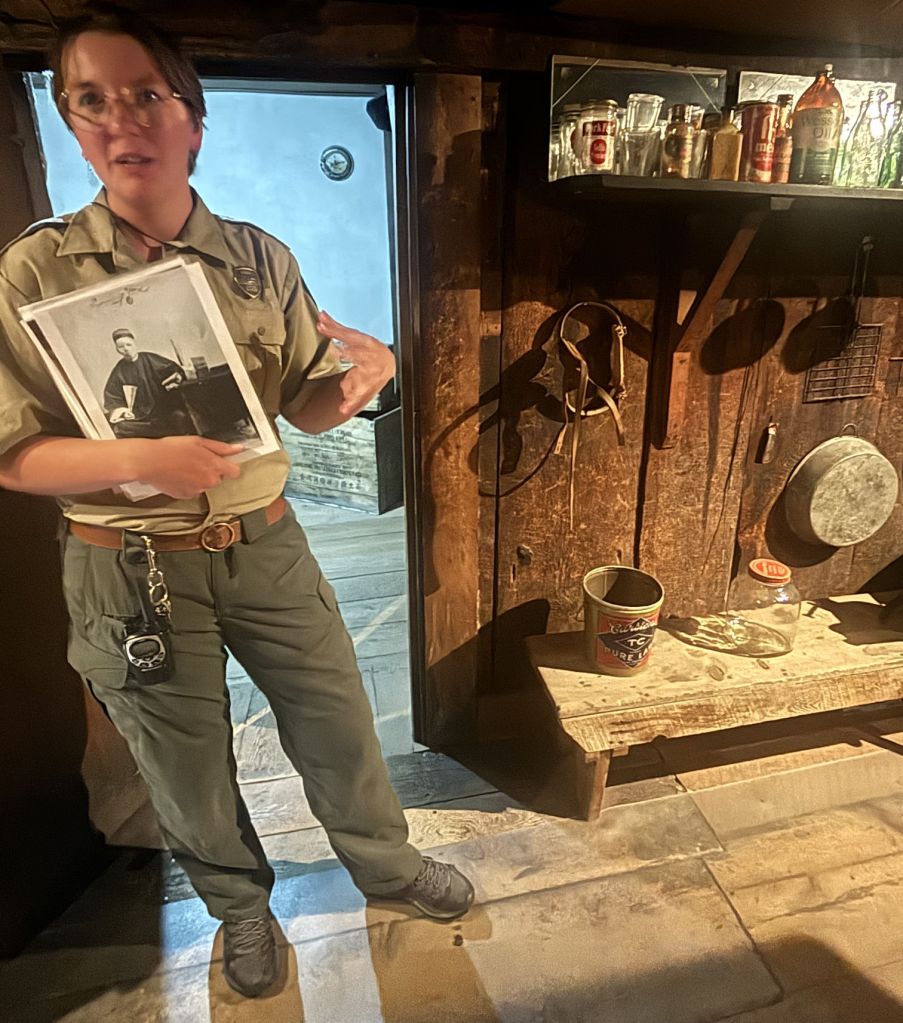

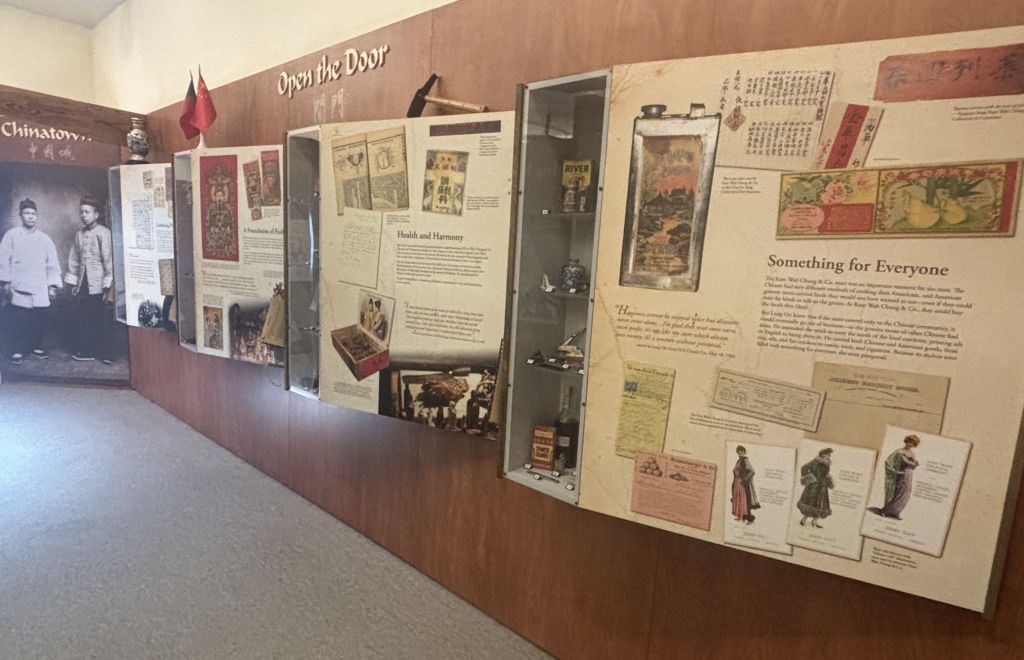

I arrived in time to catch the last tour of the day. I am grateful because visitors are not allowed inside the museum without a ranger guide. A high-quality interpretive center is nearby with documents and artifacts from the museum, and park rangers to answer questions. It remains open after the museum closed for the night. Kam Wah Chung has multiple translations online and I wish I could read Chinese. Most translations are taken from the interpretive center as Golden Flower of Prosperity, but I also saw Golden Flower of Opportunity and Golden Chinese Outpost.

In the 1880s, thousands of Chinese were suffering due to a series of wars there. Unemployment was high and families were going hungry, so men of working age took the risk to head to the United States for the Gold Rush! These ambitious Chinese were not aiming to be miners, however, but to provide support services. Their services were in great demand as they filled rolls as cooks, cleaners, and day laborers. A bustling Chinatown formed in the mining town of John Day, with an estimated 2000 Chinese residents at its peak. Those residents would be wanting to purchase their own services, and this is where business partners Doctor Wu Yunian and Liang Guangrong begin their story.

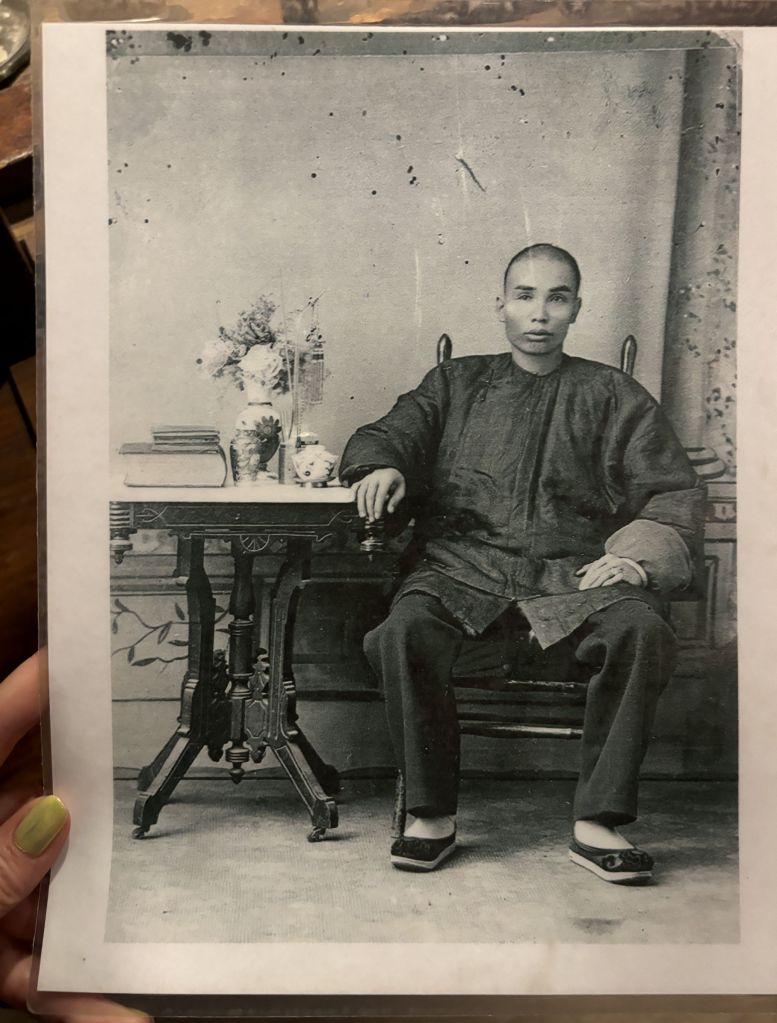

Wu Yunian (伍于念), known to the locals as Ing Hay, was born in 1862 and immigrated to Washington state, then moved on to Oregon when he was 25. He left his wife, son, and daughter in China, and never saw them again. Hay practiced pulsology, which is diagnosing and treating ailments based on pulses. He prescribed traditional Chinese herbal medicines once he diagnosed someone, and he grew a reputation for effective healing, for his good nature, civic involvement, and generosity. He earned the nickname “Doc.” He also conducted Buddhist rituals. Doctor Wu was so good at healing that he became famous and people traveled from as far as Alaska and Oklahoma to seek his care, though he was also able to diagnose and treat people by mail who wrote to him and described their symptoms.

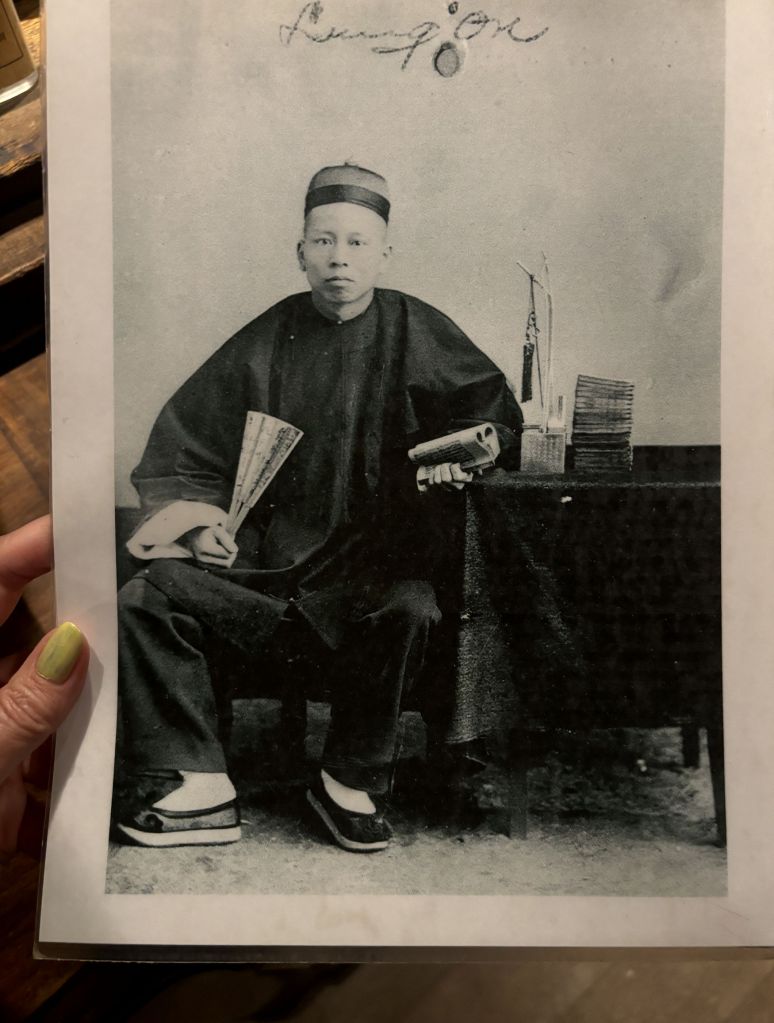

Liang Guangrong (梁光荣), who was known within the community as Lung On, was born a year after Ing Hay, and came first to California when he was 19, before moving on to Oregon. He was highly educated and from a wealthy family so he wasn’t forced to leave like so many others. He came for the adventure! Fluent in English and Chinese, his skills were valuable in many business dealings between the residents of John Day. His nickname was Leon. He worked as a translator and scribe, and wrote and read letters for people keeping in touch with their families back in China. He had a good head for business and law which helped protect him and his business, but also many other Chinese in town who sought his advice. This was a time of extreme racism against Chinese in the U.S. He also developed a reputation for a fascination with new technology – later opening the first automobile dealership in Eastern Oregon.

The two men formed a partnership in 1887, and purchased the building that likely was originally built as a trading post along a military road. Wu ran the apothecary and the spiritual services, and Liang ran the mercantile and lodging for traveling Chinese workers. Many items for sale in the store and apothecary were imported from China, a small bit of familiarity in a hostile, foreign world. By the end of the century when the gold craze dried up and the miners moved on, Wu and Liang were embedded in the community of John Day. Most of the rest of the Chinese people moved away, but the partners stayed and their business thrived, now with a whiter clientele.

As each man reached their later years, they tried to will their fortunes to their families in China, but anti-Chinese tensions made it illegal for their families to inherit, just as it had been illegal for any of their family to come to the U.S. and join them.

The list of personal and professional accomplishments by both of these men is too extensive to list. They fought discrimination as well as anyone could, and managed to make a very good life for themselves. It is clear that they both contributed greatly to the community.

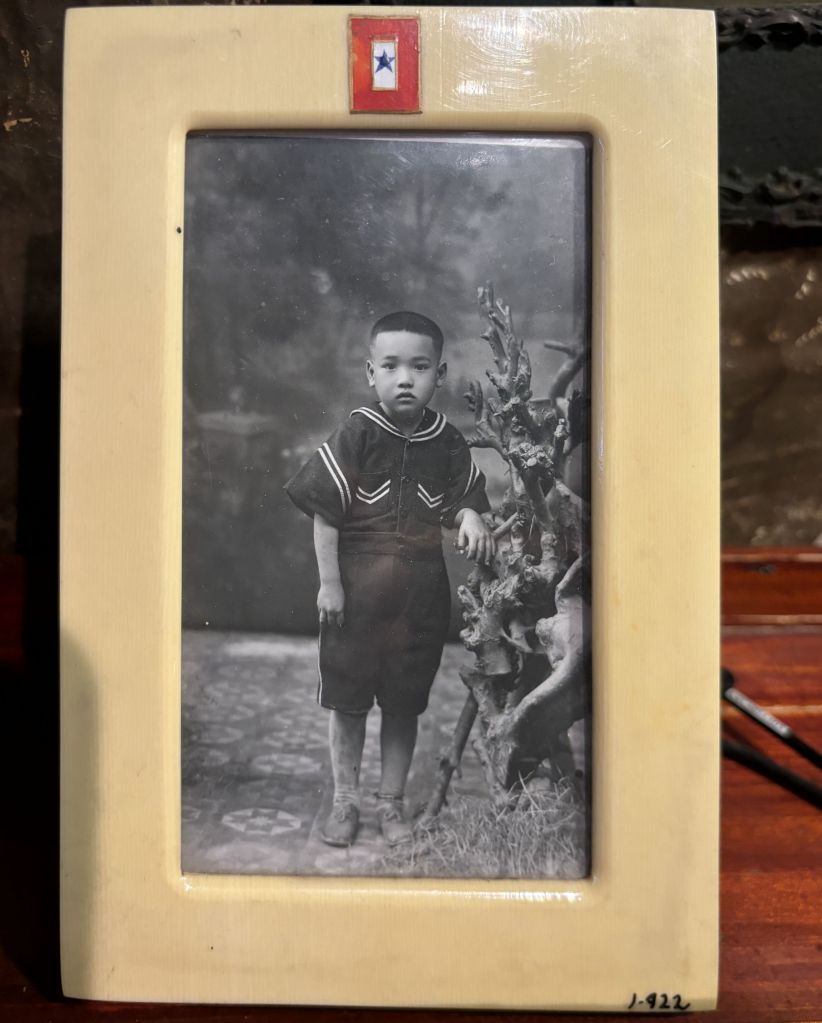

Liang died at the age of 78 in 1940. Our guide told us that, since it was really not the area of expertise for his partner, Dr. Wu did not make additional purchases after that. He would sell what was there, but in essence what remains is a time capsule from 1940.

Dr. Wu continued to grow in stature and reputation as he provided medical care in John Day, increasingly for white residents who learned to trust him. He was compelled to run the entire business by himself after losing his dear friend and partner. Though Liang had hoped his part of the business would go to his family in China, it was not allowed by U.S. law, so Wu managed it for him. Then, in 1948, Dr. Wu had a serious fall and had to go to Portland to seek treatment. He locked up the store and went to the big city.

Wu never got well enough to return to John Day, and spent the rest of his life in Portland. He died in 1952 and, still unable to give his property to family like he wanted to, in his will left the property to the city of John Day for use as a museum. But the city didn’t take advantage of the gift right away, and somehow it was forgotten. A dusty treasure of artifacts that sat only a few feet away from city managers and planners for decades.

But yes, finally, the city realized what it had and was able to put the resources needed into fulfilling the donor’s wishes. The place opened to the public as a museum in 1980. Among the documents found were a collection of uncashed checks worth $23,000 to Dr. Wu received between 1913 and 1930. No one knows why he did not cash them, aside from the fact that he did not need the money. Since it is known that he provided medical care for free for those who could not afford it, one guess is that he did not cash the checks from people who might have had financial hardship.

I got the information in this post from this website and the Oregon parks website, and from my guide, and informational panels I read at the location.

In all my years living here, and my travels multiple times through the town of John Day, learning about this bit of Oregon history just blew my mind! I am thrilled to have seen it and to now have this knowledge in my brain. I hope you enjoyed the discovery with me.

Wonderful Crystal. A great place to see. Reminded me of a bit of Australias past. I hope to go here soon with my mate if I can convince him to take a slight detour on our upcoming road trip.

Have a look if you have time

http://nnsw.com.au/winghinglong/index.html

Oh, the similarities are downright amazing between Kam Wah Chung and the Wing Hing Long museums. I hope you get a chance to get over there. Have you visited there before? I look forward to photos and a story. ❤

Yes I have but it is only open on certain days and the day I was there wasn’t that day

Fascinating and important history well recorded

Thank you Derrick! I enjoyed reading about how much philanthropy and business investments both men engaged in, which certainly helped the early development of the state of Oregon.

I love the idea of emigrating NOT for the gold rush BUT to provide support services. So very Chinese. (No generalisation warning, different cultures have different approaches…)

Thanks Crystal.

I love that, too. I remember reading, when I was young, that the people who became the richest during the Alaska gold rush were the people who set up businesses to provide supplies to mining hopefuls. At the time I thought it was brilliant. I was reminded of that history when I read this story.

I’m not surprised. Do you know where all the gold of the Incas and the Aztecs and the Mayas went? The Spaniards had hit the jackpot. All of a sudden becoming the richest nation in the then known world. Started bringing gold back to Spain. The English and the French had no gold. So they built up industry. And sold goods to Spain. Eventually all the gold crossed the border. When all the gold of the Americas had been dug out, it ended up in England and France and Spain was left with no gold and no industry… 😉