We took a taxi to the cemetery and it surprised me when Pedro had the driver let us out before we got there. Then I saw we were standing in front of a flower shop, and I recalled that we were visiting the cemetery not because it was another neat thing for tourists to see, but because his family is there.

Pedro’s father owned a funeral home, so Pedro grew up helping his dad out with the deceased from a very young age. He had grown completely accustomed to the facts of dying and dead bodies and grieving and coffins and funerals before many young people are even fully aware that people all eventually die one day. He spent many days in the Panteón Santa Paula for work as well as to honor his grandmother, his mother, his father, and his brother buried there.

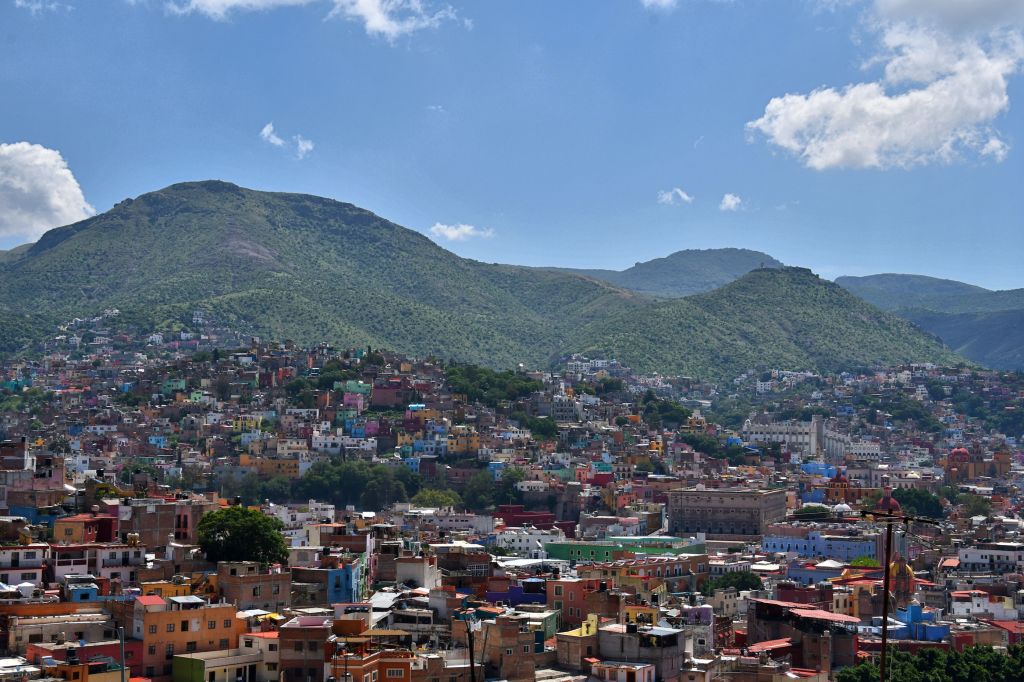

We walked a short distance up the hill from the well-placed flower shop to the Panteón. On the way, we were treated to new magnificent views of the city and the mountains beyond.

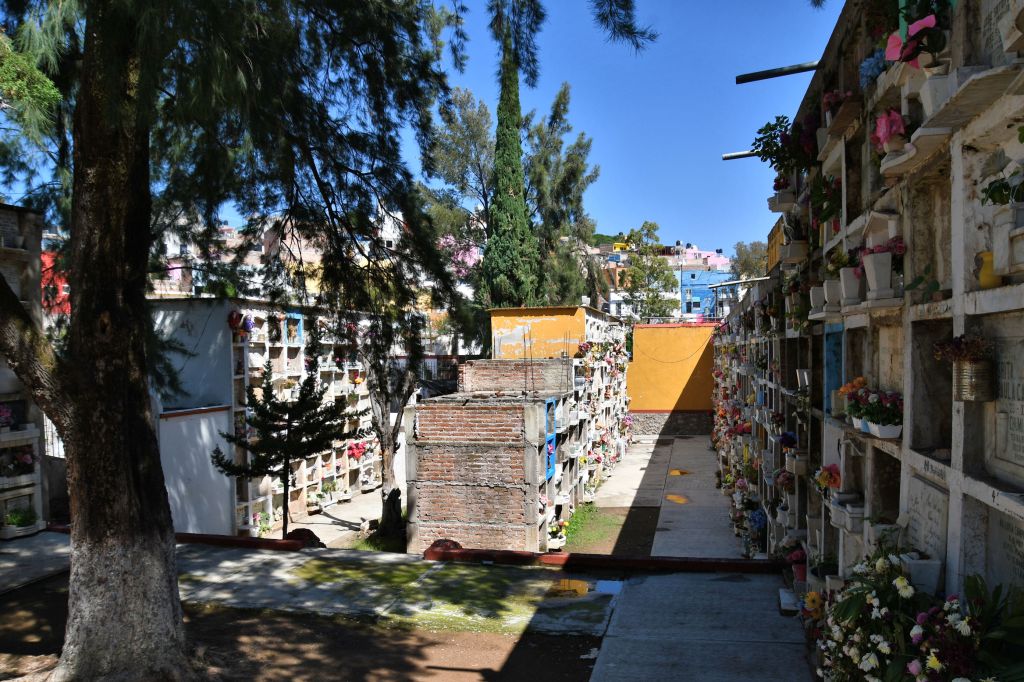

Then we arrived at the gates of the cemetery, the Municipal Pantheon of Saint Paula. The land for the cemetery was donated with the stipulation that it be named after the mother of the man who donated the land. It’s original name was Panteón de Santa Eulalia, so I wonder if the mother’s name was Eulalia or Paula. The grounds encompass 42 acres (17 hectares) and is completely surrounded by a high wall containing coffins. It holds close to 11,000 tombs.

Construction began in 1853. What makes this cemetery remarkable to me are the walls and walls of remains interred seven stories high. I have seen remains in walls before, and yet this one stands out. Apparently the choice to build it with crypts in the walls was an original plan. The entire space is surrounded by the walls of the pantheon, so it is impossible to see inside without entering the cemetery.

It is apparently the only cemetery within the city limits for a hundred years and finally the crowding was so difficult to deal with, a new cemetery was created outside of town. Pedro was able to explain a lot of the rules for this cemetery, such as how many years a body is allowed to rest unbothered, before the cavity is opened up and reused. Even if there is a fee being paid to hold a vault forever, if the cemetery cannot make contact with any descendants for a certain number of years and it appears the spot is abandoned, it will be put back into use by a new family. Frequently, members of the same family share the space. The older body will be carefully and respectfully gathered and put into a bag, and the bag is then placed inside the casket of the more recently deceased person. Then the new casket with multiple occupants goes back into the wall and the gravestone is updated.

Pedro knew the way and we followed him, through what I might describe as open air “rooms” made from walls of graves, and rows of graves standing tall and solemn, like banks of tomes in a research library. We walked down steps and through openings like doorways, and to the right, and left, finding new rooms filled with the dead, until we came to the place.

We took apart the bound flowers and spread them across the ground and created four new bundles with each type of flower divided evenly. We then emptied and cleaned the liners inside the mounted vases at each grave site, and refilled them with water. Then we placed the new flowers.

After we had spent some time here, we then walked around and explored the place. In the large main courtyard there are graves in the soil. They seemed to be the oldest of all, and also the graves of more significant people. I noticed that Florencio Antillón is buried here – the governor who lent his name to the park in a previous blog post.

The obelisk in the center of the photo above is the one you can see when walking through the entrance. It belongs to Manuel Doblado, governor of Guanajuato from September 1846 to January 31, 1847. Armando Olivares was born and died in Guanajuato in 1962. He studied at the University of Guanajuato, then was a teacher, then a rector.

Pedro thought he remembered where his grandmother was buried. He turned and walked directly to the back of one section and stopped once more in front of a grave site. He talks to us often of his grandmother, who was still around after his mother died. He has no stories to tell of his grandfather, who died before he was born.

Pedro came to a complete stop. “That table,” he said, and shook his head slowly side to side in amazement. “That table has been here forever. It’s extremely heavy, you know. It is so hard to move.”

“This is to hold the coffins,” he explained. “It’s the family’s last chance to see the body. Steps are placed near the table so they can climb up and look down into the coffin.” He said the table, La Mesa de los Requerdos (Table of Memories), is famous in the town, and he was disappointed to see it in such disrepair. It looked as if it was being used as a work table or for storage of discarded items.

I wish I could convey what it was like to watch that few moments in him. The recognition in his face. The casual intimate knowledge of an inanimate object that was real and alive for him – an integral part of a part of his life, with a role in a hundred memories. I could see him feeling the weight of the table, a boy trying to help his dad and be strong. I could see him re-watching funerals, and watching prayers said above this table. I was glad to be there for it.

The cemetery is adjacent to the Mummy Museum, and in fact is the sole source of the mummies in the museum. Pedro asked a worker in the cemetery if there was a way to get to the museum from inside of the cemetery, and was told there is no other path. We had to leave through the main entrance, and circle the outside of the cemetery to reach the museum.

“Mummies?” you ask. Yes, in my next post. ;o)

What an amazing cemetery. The front entrance is impressive. Thanks for letting me tag along 🙂

I’m glad you came along with us, Bushboy! Don’t you just love Mexicans’ approach to death? They face it directly and celebrate ancestors and bring them to life again in the ways that they honor them. I thought of that when looking at the bones and skulls in the impressive entrance. I think in the US, people would call that insensitive, and choose to pretend not to know what’s inside. But in Mexico they do not shy away from cemeteries or what they hold.

That is the best part indeed Crystal. I remember hearing about the Day of the Dead and was amazed by some of the things that happens.

I recently went to the cemetery where my family is mainly buried. The headstones, plaques really, are back to back and there were dying flowers so I didn’t want to disturb them. I found out a Jewish? custom of leaving a stone at the grave to let others know someone had visited

I think you are right about the stones being a Jewish tradition. I don’t know much about it, but I like that one too.

What a wonderful experience for you both to share. The walls are such a sensible solution, especially as the older remains can join their descendants in the newest coffins. The angel photograph is beautifully presented. I was amused at your “ghoulish detail”.