After our stop earlier in the morning, my cousin David and I turned around and headed back down from Mt. Lemmon. We made one more stop at Gordon Hirabayashi campground, in the lower slopes of Mt. Lemmon. His is a name I am so glad to learn. Mr. Hirabayashi (1918-2012) was a freaking awesome American.

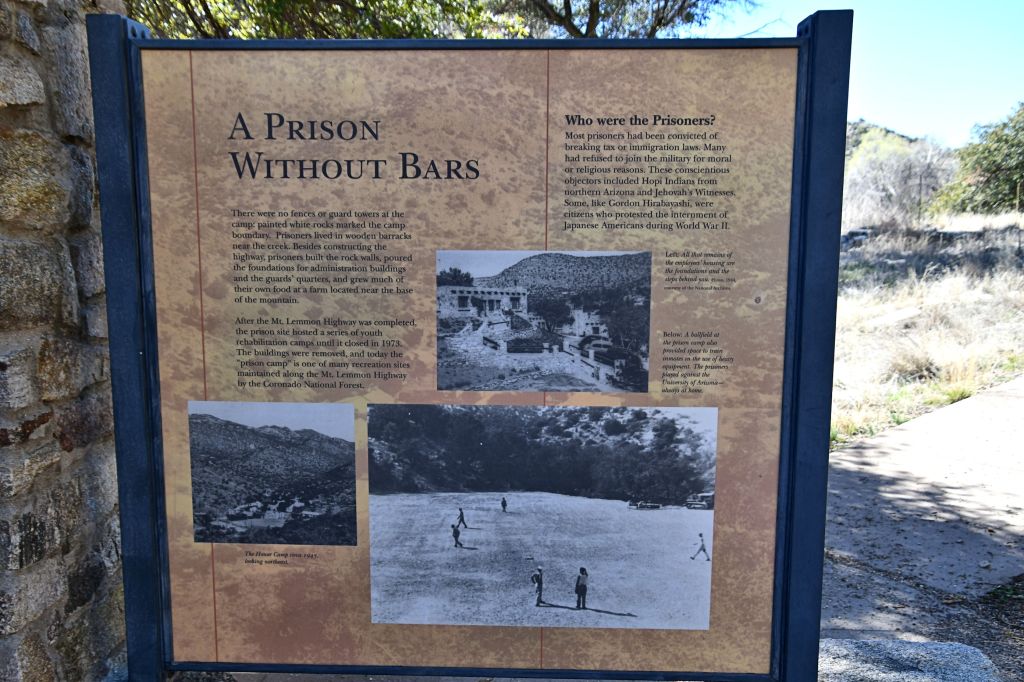

This is literally a camp site now, with places to park your RV or tent and a camp host and everything. It was originally called a “Federal Honor Camp” and what a friggin insult. There was no honor in it. David said, and I agree completely, that I could never stay here for enjoyment purposes. It is the site of an internment camp for Japanese prisoners that were forced to build the highway we had been traveling on. The camp closed in the 1970s and the buildings were sloppily razed, but David and I climbed around the hills looking for leftover remains, which are everywhere.

Gordon Hirabayashi was a senior at the University of Washington in Seattle when World War II began. He was raised as a Christian pacifist, and he registered with Selective Service as a conscientious objector. Believing himself to be protected, since he was a citizen, Hirabayashi quit school and joined a group that was assisting other Japanese families to arrange for storage and protection of their property during their imprisonment. But then he got the order to report for internment. He decided to actively resist in protest. His first act was to refuse to follow the curfew inflicted on only Japanese Americans, but not on any other Americans.

Mr. Hirabayashi said in his book A Principled Stand, “For me, my position was a positive one, that of desiring to be a conscientious citizen. It was this desire that prevented my participation in the military as a way of achieving peace and democracy and other ideals for which we stood. How could you achieve nonviolence violently and succeed?”

When it came time to report for internment, he instead turned himself in to the FBI, planning to challenge the legality of imprisoning American citizens based on their race, and using himself as a test case. He had good representation, and well-known American leaders spoke in his defense. He lost the case. Investigation found that his failure to follow curfew had been intentional protest, and thus he was convicted because failing to follow wartime orders (all the rights restrictions that had been placed on those of Japanese descent) was seen as impeding the war effort. It was a federal offense. Hirabayashi was prepared to suffer for it.

They sentenced him to 30 days in prison, and he asked if he could serve his time at a Seattle work camp instead of being put into a cell. He would only qualify if they increased his sentence to 90 days, so he agreed to that. They changed his sentence to 90 days and when he reported, they said the work camp was inside the exclusion zone (a region where no Japanese Americans were allowed), so he would have to be in a cell after all. Hirabayashi challenged this – after all, his sentence was tripled under the agreement to send him to a work camp – but he was told they couldn’t afford to send him to a camp out of state. Hirabayashi offered to get himself there, and they agreed. So this guy HITCHIKED one thousand five hundred miles to Arizona to this camp, and turned himself in. Holy Smokes. Those are some principles.

Hirabayashi appealed and his case went to the Supreme Court. There was a unanimous decision upholding Hirabayashi’s conviction on June 21, 1943.

In the camp, he joined other prisoners convicted for similar reasons: Hopi Indians and Jehovah’s Witnesses who refused to join the military, and other Nikkei, like himself, children born in the United States and thus citizens, but of Japanese heritage. Anyone with 1/16 Japanese heritage or more was considered dangerous. Citizenship protections were suspended for the war. While interned here, Hirabayashi received a “loyalty questionnaire,” a letter sent only to Japanese Americans, designed to test their loyalty and see if they were good enough to be conscripted. He continued his protest and returned the questionnaire blank, along with a letter explaining that it was unconstitutional to ask only Japanese Americans to complete it. His protest was ignored and he was drafted and ordered to report for military service. His continued refusal concluded in a year at McNeil Island Penitentiary.

Prison camp workers’ main task was to build the highway up this mountain. It reminds me of the Russian Highway that Manja showed Pedro and me on in Slovenia – so called because it was built by Russian prisoners during the first World War. Here at the honor camp, the interned were provided with pick axes, shovels, and wheelbarrows. The information kiosk quotes one prisoner as saying, “Before I came here, I thought prisoners only broke rocks with picks in cartoons.” Eventually heavier equipment was brought in.

I wrote about another interned American citizen, Kennie Namba, when I visited the cherry blossoms in downtown Portland. While writing that post, I asked rhetorically, how could so many Japanese Americans submit to internment? I was wrong! So many of them did resist, and Mr. Hirabayashi was one primary example. There are 300 Japanese Americans on record who refused to be drafted into the military as a form of civil disobedience until their rights were restored. It did not work, and only convinced the government that these were dangerous people and they were all sentenced to prison time, often served in these “honor camps.”

I was practically glowing in the sunshine beneath the deep blue skies. I happily photographed anything my cousin pointed out. David was a master at spotting birds. Well, my eyes are not very good at distance viewing. But beyond that, it was clear that practice makes a big difference when it comes to spotting birds perched in trees. He could identify them at 50 yards within 3 seconds.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was signed into law on August 10, 1988, by President Ronald Reagan, citing “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a lack of political leadership” as causes for the incarceration. Gordon Hirabayashi said, “If you forget about it, you’re more vulnerable to having it repeated, and we don’t want to have this ever happen to any citizen again.” In all, 125,284 people of Japanese descent were held in internment camps following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. “I never looked at my case as my own, or just as a Japanese American case. It is an American case, with principles that affect the fundamental human rights of all Americans.”

Every time one of our leaders encourages us to identify groups of people that are not as good as other groups (e.g. transgender people, Jewish people, people with brown skin, people whose heritage is from a different country), then we are heading down the path toward a future where it might seem ok to lock them up just to be safe. Let’s not agree to these kinds of divisions, or leaders who encourage us to point fingers at others. Ok?

Bird Count: That’s four more new birds identified in a single hour. As of halfway through day four in Arizona, my bird count is up to ten.

A great story Crystal. The bird count is getting up there 👍😀

Thanks! It’s getting more fun to count birds now that the numbers are going up!

David’s persistence and this post go some way to combatting those who tried to erase this history from memory

Thank you. I was surprised to learn all this history from a simple stop to photograph birds. I am grateful that I have this blog, to keep telling the story.

Great post! Thanks for the introduction to Mr. Hirabayashi. Very interesting, and I hope our country remembers the lessons we’ve learned! I’m heading to Tucson soon, so I’ve enjoyed binge reading your latest posts. Have a terrific day!

Lenore! I am so excited that you get to go to Tucson! It was my first-ever visit. I never even saw the city itself, ha ha. David lives in the suburbs, and I think maybe once we drove through the city, but mostly we went to the desert. I know I will have to go again. I hope you have a blast, and don’t get a sunburn, like I did. 🙂